trans-render

trans-render (abbreviation: TR) provides a methodical way of instantiating a template. It draws inspiration from the (least) popular features of XSLT. Like XSLT, TR performs transforms on elements by matching tests on elements. Whereas XSLT uses XPath for its tests, tr uses css path tests via the element.matches() and element.querySelector() methods. Unlike XSLT, though, the transform is defined with JavaScript, adhering to JSON-like declarative constraints as much as possible.

XSLT can take pure XML with no formatting instructions as its input. Generally speaking, the XML that XSLT acts on isn't a bunch of semantically meaningless div tags, but rather a nice semantic document, whose intrinsic structure is enough to go on, in order to formulate a "transform" that doesn't feel like a hack.

Likewise, with the advent of custom elements, the template markup will tend to be much more semantic, like XML. trans-render's usefulness grows as a result of the increasingly semantic nature of the template markup, because often the markup semantics provide enough clues on how to fill in the needed "potholes," like textContent and property setting, without the need for custom markup, like binding attributes. But trans-render is completely extensible, so it can certainly accommodate custom binding attributes by using additional, optional helper libraries.

This can leave the template markup quite pristine, but it does mean that the separation between the template and the binding instructions will tend to require looking in two places, rather than one. And if the template document structure changes, separate adjustments may be needed to keep the binding rules in sync. Much like how separate style rules often need adjusting when the document structure changes.

Advantages

TR will certainly take advantage of phase I of template instantiation when it's available. TR sees itself as either an alternative, or a supplement, to any kind of inline binding future phases of template instantiation support.

By keeping the binding separate, the same template can thus be used to bind with different object structures.

Providing the binding transform in JS form inside the transform function signature has the advantage that one can benefit from TypeScript typing of Custom and Native DOM elements with no additional IDE support. As much as possible, JSON-like structures are also used, allowing most or all of the binding to remain declarative.

Another advantage of separating the binding like this is that one can insert comments, console.log's and/or breakpoints, making it easier to walk through the binding process.

For more musings on the question of what is this good for, please see the rambling section below.

NB It's come to my attention (via template discussions found here) that there are some existing libraries which have explored similar ideas:

Workflow

trans-render provides helper functions for either 1) cloning a template, and then walking through the DOM, applying rules in document order, or, 2) using the same syntax, applying changes on a live DOM fragment. Note that the document can grow as processing takes place (due, for example, to cloning sub templates). It's critical, therefore, that the processing occur in a logical order, and that order is down the document tree. That way it is fine to append nodes before continuing processing.

As such, trans-render could (in theory) be used to augment/finesse the results of template.createInstance of the template instantiation proposal.

Drilling down to children

For each matching element, after modifying the node, you can instruct the processor which node(s) to consider next.

Most of the time, especially during initial development, you won't need / want to be so precise about where to go next. Generally, the pattern, as we will see, is just to define transform rules that match the HTML Template document structure pretty closely.

So, in the example we will see below, this notation:

const Transform = {

details: {

summary: 'Hallå'

}

};

means "if a node has tag name 'details', then find any direct children of the details tag that has tag name 'summary', and set its textContent property to 'Hallå'." Let's show the full syntax for a minimal working example:

Syntax Example:

<template id="sourceTemplate">

<details>

...

<summary>E pluribus unum</summary>

...

</details>

</template>

<div id="target"></div>

<script type="module">

import { transform } from 'trans-render/transform.js';

const model = {

summaryText: 'hello'

}

const Transform = {

details: {

summary: model.summaryText

}

};

transform(sourceTemplate, { Transform }, target);

</script>

Produces

<div id="target">

<details>

...

<summary>hello</summary>

...

</details>

</div>

Not limited to declarative syntax

The transform example so far has been declarative (according to my definition of that subjective term). This library is striving to make the syntax as declarative as possible as more functionality is added. The goal being that ultimately much of what one needs with normal UI development could in fact be encoded into a separate JSON import.

However, bear in mind that the transform rules also provide support for 100% no-holds-barred non-declarative code:

const Transform = {

details:{

summary: ({target}: RenderContext<HTMLSummaryElement>) => {

///knock yourself out

target.appendChild(document.body);

}

}

}

Template Stamping

If using trans-rendering for a web component, you will very likely find it convenient to "stamp" a significant number of individual elements of interest. The quickest way to do this is via the templStamp plugin:

import {templStampSym} from 'trans-render/plugins/templStamp.js';

...

const uiRefs = {mySpecialElement1: Symbol(), mySpecialElement2: Symbol()};

const Transform = {

':host': [templStampSym, uiRefs]

}

This will search the template / DOM fragment / matching target for all elements whose id or "part" attribute is "mySpecialElement1" or "mySpecialElement2". Only one element will get stamped for each reference later. In other words, stamping is only useful if you have exactly one element whose id or part is equal to "mySpecialElement1".

A reassessment of this functionality will take place with the advent of DOM Parts.

Here we also see the concept of being able to extend the trans-render library, while sticking to quite strict declarative syntax.

How declarative is this, really?

The syntax:

const Transform = {

':host': [templStampSym, uiRefs]

}

has no side effects from loading. It could be turned into JSON if JSON had native support for Symbols. Being that it doesn't, some sort of custom solution for symbols would be required, similar to working with dates. The plugin symbol should be of type Symbol.for([guid]). Likewise, the uiRefs would probably also require adopting Symbol.for([guid]).

Why use a plugin for this convenient functionality?

Here's the thinking for why this convenient plugin is not part of the core trans-render syntax: The core syntax is attempting to stick with rules which apply locally to the contextual DOM node. This plug-in, on the other hand, traverses the whole DOM of the DOM fragment for matches. So this syntax isn't compatible with parsers that work with low memory streams, which could be useful if and when browsers can easily stream HTML into any arbitrary element.

Later we will see a more SAX-compliant (but more tedious) way of creating symbolic UI references.

Syntax summary

We'll be walking through a number of more complex scenarios, but for reference, the rules are available below in summary form, if you expand the section.

They will make more sense after walking through examples, and, of course, real-world practice.

Rules Summary

Terminology:

Each transform rule has a left hand side (lhs) "key" and a right hand side (rhs) expression.

For example, in:

const Transform = {

details: {

summary: model.summaryText

}

};

details, summary are lhs keys of two nested transform rules. model.summaryText is a rhs expression, as is the open and closed curly braces section containing it.

In the example above, the details and summary keys are really strings, and could be equivalently written:

const Transform = {

'details': {

'summary': model.summaryText

}

};

Due to the basic rules of object literals in JavaScript, keys can only be strings or ES6 symbols (or numbers, which aren't used). trans-render uses both strings and ES6 symbols as keys.

LHS Key Scenarios

- If the key is a string that starts with a lower case letter, then it is a "css match" expression.

- If the key starting with a lower case letter ends with the word "Part", then it maps to the css match expression: '[part="{{first part of the key before Part}}"]'

- If the key = ":host" then it selects the hosting web component.

- If the key is of the form (:has(...)), then a querySelector is tried with the inner expression.

- If the key is a string that starts with double quote, then it is also a "css match" expression, but the css expression comes from the nearest previous sibling key which doesn't start with a double quote.

- If the key is a string that starts with a capital letter, then it is part of a "Next Step" expression that indicates where to jump down to next in the DOM tree.

- If the key is a string that starts with ^ then it matches if the tag name starts with the rest of the string [TODO: do we need with introduction of Part notation above?]

- If the key is a string that ends with $ then it matches if the tag name ends with the rest of the string [TODO: do we need with introduction of Part notation above?]

- If the key is "debug" then set a breakpoint in the code at that point.

- If the key is an ES6 symbol, it is a shortcut to grab a reference to a DOM element previously stored either in context.host or context.cache, where context.host is a custom element instance.

CSS Match Rules

- If the rhs expression is null or undefined, do nothing.

- If the rhs expression evaluates to a string, then set the textContent property of matching target element to that string.

- If the rhs expression evaluates to the boolean "false", then remove the matching elements from the DOM Tree.

- If the rhs expression evaluates to a symbol, create a reference to the matching target element with that symbol as a key, in the ctx.host (custom element instance) or ctx.cache property.

- If the rhs expression evaluates to a function, then

- that function is invoked, where the context object is passed in

- The evaluated function replaces the rhs expression.

- If the rhs expression evaluates to an array, then

- Arrays are treated as "tuples" for common requirements.

- The first element of the tuple indicates what type of tuple to expect.

- If the first element of the tuple is undefined, just ignore the rest of the array and move on.

- If the first element of the tuple is a non-array, non HTMLTemplateElement object, then the tuple is treated as a "PEATS" tuple -- property / event / attribute / transform / symbol reference setting:

- First optional parameter is a property object, that gets shallow-merged into the matching element (target).

- Shallow-merging goes one level deeper with style and dataset properties.

- Second optional parameter is an event object, that binds to events of the matching target element.

- Third optional parameter is an attribute object, that sets the attributes. "null" values remove the attributes.

- Fourth optional parameter is a sub-transform, which recursively performs a transform within the light children of the matching target element.

- Fifth optional parameter is of type symbol, to allow future referencing to the matching target element.

- First optional parameter is a property object, that gets shallow-merged into the matching element (target).

- If the first element of the tuple itself is an array, then the tuple represents a declarative loop associated with the array of items in the first tuple element.

- The acronym to remember for a loop array is "ATRIUMS".

- First element of the tuple is the array of items to loop over.

- Second element is either:

- A template reference that should be repeated, or

- A tag of type string, that turns into a DOM element using document.createElement(tag)

- A toTagOrTemplate function that returns a string or template.

- If the function returns a string, it is used to generate a (custom element) with the name of the string.

- If the function returns a template, it is the template that should be repeated.

- Third optional parameter is an optional range of indexes from the item array to render [TODO].

- Fourth optional parameter is either:

- the init transform for each item, which recursively uses the transform syntax described here, or

- a symbol, which is a key of ctx, and the key points to a function that returns a transform.

- Fifth optional parameter is the update transform for each item.

- Sixth optional parameter is metadata associated with the array we are looping over -- how to extract the identifier for each item, for example.

- Seventh optional parameter is a symbol to allow future referencing to the matching target element.

- If the first element of the tuple is a function, then evaluate the function, passing in the render context, and the returned value of the function replaces the first element.[TODO]

- If the first element of the tuple is a boolean, then this represents a conditional display rule.

- The acronym to remember for a conditional array is "CATMINTS".

- The first element is the condition.

- The second element is where it looks for the affirmative template.

- The third element contains metadata instructions.

- The fourth element is where it looks for the negative template.

- If the first element is true, then the affirmative template is cloned into the target.

- If the first element is false, then the negative template is cloned into the target.

- The third element of the array allows for "metadata instructions". Currently it supports stamping the target with a "yesSymbol" and a "noSymbol", depending on the value of the condition, which later transform steps can then act on.

- A major TODO item here is if using a conditional expression as part of an update transform, how to deal with previously cloned content, out of sync with the current value of the condition.

- If the first element of the tuple is an ES6 symbol, then this represents a directive / plugin.

- The syntax only does anything if:

- that symbol, say mySymbol, is a key of the ctx object, and

- ctx[mySymbol] is of type function.

- If that is the case, then that function is passed ctx, and the remaining items in the tuple.

- The benefits of a directive over an using an arrow function combined with an imperative function call are:

- Arrow functions are a bit cumbersome

- Arrow functions are not really as declarative (kind of a subjective call), possibly less capable of being encoded as JSON.

- I am under some foggy assumption here that global Symbol.for([guid string])'s can be represented in JSON somehow, based on some special notation, like what is done for dates.

- The syntax only does anything if:

- If the first element of the tuple is a string, then this is the name of a DOM tag that should be inserted.

- The second optional element is the position of where to place the new element relative to the target -- afterEnd, beforeEnd, afterBegin, beforeBegin, or replace [TODO: no test coverage]

- The third optional element is expected to be a PEATS object if it is defined.

NB 1: Typescript 4.0 is adding support for labeled tuple elements. Hopefully, that will reduce the need to memorize words like "Peat", "Atrium", "Catmint", "Roy G Biv," etc, and what the letters in those words stand for.

NB 2: A promising tuple related tc39 proposal is gaining momentum. If implemented, it will likely affect the rules above to some degree.

Multiple matching with "Ditto" notation

Sometimes, one rule will cause the target to get (new) children. We then want to apply another rule to process the target element, now that the children are there.

But uniqueness of the keys of the JSON-like structure we are using prevents us from listing the same match expression twice.

We can specify multiple matches as follows:

import { transform } from '../transform.js';

const Transform = {

details: {

article: articleTemplate,

'"': ({target}) => ...,

'""': ...,

'"3': ...

}

};

transform(sourceTemplate, { Transform }, target);

I.e. any selector that starts with a double quote (") will use the last selector that didn't.

Simple Template Insertion

A template can be inserted directly inside the target element as follows:

<template id="summaryTemplate">

My summary Text

</template>

<template id="sourceTemplate">

<details>

...

<summary></summary>

...

</details>

</template>

<div id="target"></div>

<script type="module">

import { transform } from '../transform.js';

const Transform = {

details: {

summary: summaryTemplate

}

};

transform(sourceTemplate, { Transform }, target);

</script>

Here we are relying on the fact that outside any Shadow DOM, id's become global constants. So for simple HTML pages, this works. Assuming HTML Modules someday bring the world back into balance, an open question remains how code will be able to reference templates defined within the HTML module.

For now, typically, web components are written in JavaScript exclusively. Although creating a template is one or two lines of code, the code is a bit lengthy, so a utility to create a template is provided that can then be referenced. This allows the repetitive, scandalous code, required in lieu of an HTML Template DOM node, to be hidden from view.

If you don't use shadowed template insertion or slotted template insertion mentioned below, then the way the template cloning works is this:

- Cloned content is inserted inside a tag called template-content.

- Attribute 'part=content' is added to the template-content tag.

- Old matching template-content's are hidden rather than deleted, via display: none, and attribute part=content is removed.

These observations are important if you plan to do some node matching on the (newly) created content.

You will need to add a rule that looks something like:

const Transform = {

details: {

summary: summaryTemplate,

'"':{

contentPart:{

...

}

}

}

};

Shadowed Template Insertion

<template id="articleTemplate" data-shadow-root="open">

<slot name="adInsert"></slot>

My interesting article...

</template>

<template id="sourceTemplate">

<details>

...

<summary></summary>

<article>

<iframe slot=adInsert></iframe>

</article>

...

</details>

</template>

<div id="target"></div>

<script type="module">

import { init } from '../init.js';

const Transform = {

details: {

article: articleTemplate

}

};

init(sourceTemplate, { Transform }, target);

</script>

When ShadowRoot is attached to the article element, the children can then be slotted into the ShadowDOM, which is quite convenient.

Limited support for Slotted content when not using ShadowDOM (WIP)

It is unfortunate that use of slots is tightly coupled with ShadowDOM, when it comes to native support. Vue.js and Svelte appear to demonstrate that the slot concept is useful beyond ShadowDOM support.

TR supports limited slot support outside the bounds of ShadowDOM. For now the only support is this:

If template insertion (mentioned above) is applied to an element that already has children, and if the inserted template has at least one slot element, the original children replace the slot elements, based on similar (first order) rules to Shadow DOM slotting. A slot with attribute "as-template" will be converted to a template element.

This can be quite useful in converting compact loop syntax into clunkier markup that a web component may require:

<template id=repeatTemplate>

<my-repeater-element>

<slot as-template></slot>

</my-repeater-element>

</template>

<template id=mainTemplate>

<ul>

<li foreach item in items>

<span data-field=item.name></span>

</li>

</ul>

</template>

<script>

const Transform = {

':has(> [foreach])': repeatTemplate

}

</script>

produces:

<ul>

<my-repeater-element>

<template>

<li foreach item in items>

<span data-field=item.name></span>

</li>

</template>

</my-repeater-element>

</ul>

Unlike the more powerful native ShadowDOM, once the children are merged into the slots, there's no longer a distinction between light children and shadow children. So non-shadow slotting makes the most sense when used during the init transform.

Arbitrary queries.

If most of the template is static, but there's an isolated, deeply nested element that needs modifying, it is possible to drill straight down to that element by specifying a "Select" string value, which invokes querySelector. But beware: there's no going back to previous elements once that's done (within that nested transform structure).

Jumping arbitrarily down the document tree can be done with a "NextStep" object:

const Transform = {

article: {

Select: 'footer',

Transform: {

'p.contact': model.author.email

}

}

};

In the example above, when the transformer encounters an article tag, it will then do a querySelect for the first element matching "footer".

It then checks within the direct children of footer for elements matching css selector "p.contact". If such an element is found, then the textContent is set to model.author.email (where "model" is assumed to be some object in scope).

The object:

{

Select: ...

Transform: ...

}

is a "NextStep" object, and can be easily distinguished from a nested transform object with CSS selector keys (as the previous examples showed) by the presence of capital letters for the keys. The options of the NextStep object are as shown:

export interface NextStep {

Transform?: TransformRules,

NextMatch?: string,

Select?: TransformRules | null,

MergeTransforms?: boolean,

SkipSibs?: boolean,

}

Matching next siblings

We most likely will also want to check the next siblings down for matches. Previously, in order to do this, you had to make sure "matchNextSibling" was passed back for every match. But that proved cumbersome. The current implementation checks for matches on the next sibling(s) by default. You can halt going any further by specifying "SkipSibs" in the "NextStep" object discussed above, something to strongly consider when looking for optimization opportunities.

It is deeply unfortunate that the DOM Query Api doesn't provide a convenience function for finding the next sibling that matches a query, similar to querySelector or closest. Just saying. But some support for "cutting to the chase" laterally is also provided, via the "NextMatch" property in the NextStep object.

Matching everything

Note the transform rule:

Transform: {

'*': {

Select: '*'

},

The expression "*" is a match for all HTML elements. What this is saying is "for any element regardless of css-matching characteristics, continue processing its first child (Select => querySelector('*')). This, combined with the default setting to match all the next siblings means that for a "sparse" template with very few pockets of dynamic data, you will be doing a lot more element matching than needed, as every single HTMLElement node will be checked for a match. But for initial, pre-optimization work, this transform rule can be a convenient way to get things done more quickly.

If you use a rule like the one above, then the other selector rules will almost exactly match what you would expect with a classic css file. In the absense of such a rule, css selectors will flow most naturally if emulating the nested support provided by tools such as SASS.

At this point, only a synchronous workflow is provided (except when piercing into ShadowDOM).

What does wdwsf stand for?

As you may have noticed, some abbreviations are used by this library:

- init = initialize

- ctx = (rendering) context

- idx = (numeric) index of array

- SkipSibs = Skip Siblings

- attribs = attributes

- props = properties

- refs = references

The ctx object has a "mode" property that becomes "update" after the initial transform completes.

Use Case 1: Applying the DRY principle to (post) punk rock lyrics

Example 1a

Demonstrates including sub templates.

Example 1b

Demonstrates use of update, rudimentary interpolation, recursive select.

Conditional Display

Permanent Removal

If a matching node returns a boolean value of false, the node is removed. For example:

...

"section[data-type='attributes']":false

...

Here the tag "section" will be removed.

NB: Be careful when using this technique. Once a node is removed, there's no going back -- it will no longer match any css if you use trans-render updating (discussed below). If your use of trans-render is mostly to display something once, and you recreate everything from scratch when your model changes, that's fine. However, if you want to apply incremental updates, and need to display content conditionally, it would be better to either use a custom element for that purpose, or utilize the conditional template support shown below.

Lazy loading (and limited support for conditional display)

article: [isHotOutside, warmWeatherTemplate,, coldWeatherTemplate]

You can also do different sub transforms within the article element:

article: [isHotOutside, warmWeatherTransform,, coldWeatherTransform]

The missing element, after the warmWeather[Template|Transform], allows for a choice of reference symbols to be established for the target element (article in this case),

Property / attribute / event binding

import { transform} from '../transform.js';

const Transform = {

details: {

'my-custom-element': [ //Hi!

//Prop Setting

{prop1:{greeting: 'hello'}, prop2:'hello', },

//Event Handler Setting

{click: this.clickHandler},

//Attribute Setting

{'my-attribute': 'myValue', 'my-attribute2': true, 'my-old-attribute': null}, // null removes attribute

//Transform or NextStep Object

{

'my-light-child': ...

}

]

}

};

transform(sourceTemplate, { Transform }, target);

Here, 'my-custom-element' is a custom element, and the array starting with [ //Hi! it matches to is treated as a tuple (and tuple support in JS and TypeScript seems to be gaining momentum). An easy to remember trick for this particular Tuple is: "PEAT", which stands for prop setting, event handler setting, attribute setting, transform.

The first element of the tuple must be a JS Object, not undefined or null. I.e. if it is undefined, the rest of the array will be ignored.

Tip: If the first element of the tuple binds to some optional property, which might be undefined or null, you can ensure that the array be treated as a "PEAT" array by adding a union with an empty {}. I.e.

const settings = {...}

const Transform = {

'my-custom-element':[settings.somePropThatMightBeUndefined || {}]

}

Although the first element of the tuple can't be undefined, each of the renaming elements of the tuple are "optional" in the sense that you can either end the array early, or you can skip over one or more of the settings by specifying an empty object ({}), or just a comma i.e. [{},,{'my-attribute', 'myValue'}].

A suggestion for remembering the order these "arguments" come in -- Properties / Events / Attributes / Transform can be abbreviated as "PEAT." Actually, there is a fifth "argument" of type symbol, which stores the target in ctx.host. So the acronym to remember is really PEATS.

The second element of the array, where event handlers can go, can actually pass arguments to the handler:

{click: [this.selectNewKey, val: 'dataset.keyName']}

which could allow the event handler to actually be a regular method expecting a parameter.

class MyCustomElement extends XtalElement{

selectNewKey(key: string){

...

}

}

In this case, it would be a string parameter, since target.dataset.keyName will be of type script. val supports a simple a.b.c type expressions, read fro the current matching target element. The actual event object is still available as the second parameter of the method.

If a third argument is provided, it is assumed to be a function which does some kind of conversion of the value extracted from the target:

{click: [this.setAge, val: 'dataset.age', parseInt]}

class MyCustomElement extends XtalElement{

setAge(age: number){

...

}

}

A more verbose but somewhat more powerful way of setting properties on an element is discussed with the decorate function discussed later.

Prop setting shortcut [No test coverage]

We mentioned earlier that if a css match maps to a string, we do the most likely thing one would want -- setting the textContent:

const Transform = {

details: {

summary: 'Hallå'

}

};

But it is also desirable to have a fast way of setting properties with few required keystrokes.

This can be done as follows.

If the template contains this markup, with a "pseudo" attribute starting with a dash:

<template>

<my-custom-element -my-prop></my-custom-element>

</template>

const Transform = {

'my-custom-element[-my-prop]':{

subProp1: 'hello',

subProp2: 'world'

}

}

Then the property "myProp" of the my-custom-element instance will be set to {subProp1:'hello', subProp2: 'world'}.

In addition to the slightly less typing required to set property values, there is also the advantage that the template provides fairly non-obtrusive clues in the markup as to what is happening.

Contextual, Synchronous Evaluation

All of the rules listed above also apply to the result of evaluating a lambda expression:

const Transform = {

details: {

summary: ({ctx}) => ctx.summaryText

}

}

ctx is an object meant to pass data through (repeated, nested) transforms. It includes a number of internal, reserved properties.

TypeScript Tip: Some of the properties of ctx, like target, are quite generic (e.g. target:HTMLElement, item: any). But one can add more specific typing thusly:

summary: ({target, item} : {target: HTMLInputElement, viewModel: MyModel, item: MyModelItem}) =>{

...

}

The argument is of type "RenderContext" so you can also get the benefit of typing thusly:

summary: ({target, item} : RenderContext<HTMLInputElement, MyModelItem>) =>{

...

}

Planting flags

It was mentioned earlier that there is a plugin, templStamp, that can map large swaths of uniquely named (via id or part attribute) elements to symbols for later use.

This can alo be done on an individual element basis, with no plugin required:

const myFastAccessSymbol = Symbol();

initTransform = {

'my-rapidly-changing-element': myFastAccessSymbol

}

updateTransforms = [{

({fastChangingProp}) =>{

[myFastAccessSymbol]: ({target}) => target.myProp = fastChangingProp

}

}]

Multiple matching with "More" symbol [TODO: No Test coverage]

Previously, we provided a strategy for matching duplicate css selectors, using "ditto" notation. But what about symbol keys? That won't work.

Instead, do the following:

import {transform, more} from 'trans-render/transform.js';

...

updateTransform = {

[mySymbol]: [do something],

[more]:{

[mySymbol]: [do something else]

}

}

Replacing / inserting tags declaratively

One functionality that trans-render considers of utmost importance is the ability dynamically replace one tag with another elegantly.

Examples of where tag substitution is useful are:

- Cases where "polymorphism" between a similar family of tags is required.

- Extending basic functionality, using built-in native HTML elements, with more functional, visually appealing design libraries.

- Using version specific custom elements, in a micro-front-end environment (i.e. supporting parallel versions).

This is best done before a template's clone has been inserted into the live DOM tree, but trans-render imposes no rules on when it can be done.

Example syntax:

const initTransform = {

...

'my-element': [MyElement.isReally, 'replace'],

...

}

In addition to replacing a tag, you can instead insert a tag, and specify the location relative to the target. E.g.:

const initTransform = {

...

details: ['summary', 'afterBegin'],

'"':{

summary:'Summary text'

}

...

}

Utility functions

Create template element programmatically

createTemplate(html: string, context?: any, symbol?: symbol)

Example:

details: ({ctx}) => createTemplate(`<summary>SummaryText</summary>...`, ctx);

An explanation for the second and third parameters is needed.

Templates shine most when they are created once, and cloned repeatedly as needed. What this means, in the context of a JS module, is that they should be cached somewhere, and instances cloned from the cache. The use of the third parameter, symbol, ensures that no two disparate code snippets will trample over each other. But which "cache" to use? The easiest, sledgehammer approach would be to cache it in self or globalThis. But there is likely a cost to caching lots of things in such a global area, as the lookups are likely to grow (logarithmically perhaps).

Caching inside the renderContext object (ctx) may be too tepid, because the renderContext is likely to be created with each instance of a web component.

So the code checks whether the context object has a "cache" property, and if so, it caches it there. If using this library inside a web component library, a suggestion would be to set ctx.cache = MyCustomElementClass.

Simple Loop support

Imperative Repeat

repeat(

template: HTMLTemplateElement | [symbol, string],

ctx: RenderContext,

countOrItems: number | any[],

target: HTMLElement,

initTransform: TransformValueOptions,

updateTransform: TransformValueOptions = initTransform

)

The next big use case for this library is using it in conjunction with a virtual scroller. As far as I can see, the performance of this library should work quite well in that scenario.

However, no self respecting rendering library would be complete without some internal support for repeating lists. This library is no exception. While the performance of the initial list is likely to be acceptable, no effort has yet been made to utilize state of the art tricks to make list updates keep the number of DOM changes at a minimum.

Anyway the syntax is shown below. What's notable is a sub template is cloned repeatedly, then populated using the simple init / update methods.

<div>

<template id="itemTemplate">

<li></li>

</template>

<template id="list">

<ul id="container"></ul>

<button id="addItems">Add items</button>

<button id="removeItems">Remove items</button>

</template>

<div id="target"></div>

<script type="module">

import { init } from '../init.js';

import { repeat } from '../repeat.js';

import { update } from '../update.js';

const options = {matchNext: true};

const itemTransform = {

li: ({ item }) => 'Hello ' + item.name,

};

const ctx = init(list, {

Transform: {

ul: ({ target, ctx }) => repeat(itemTemplate, ctx, 10, target, itemTransform) // or repeat(itemTemplate, ctx, items, target, itemTransform)

}

}, target, options);

ctx.update = update;

addItems.addEventListener('click', e => {

repeat(itemTemplate, ctx, , container, itemTransform);

});

removeItems.addEventListener('click', e =>{

repeat(itemTemplate, ctx, 5, container);

})

</script>

</div>

Declarative Repeat

Please expand below

Declarative Repeat [Partially Implemented]

const ctx = init(list, {

Transform: {

ul: [items, itemTemplate, [3, 10], itemTransform,,, ul$]

}

}, target, options);

Acronym: ATRIUMS

Array (of items) Template (per item) Range Init Transform Update Transform Metadata Symbol Ref

Logan's Loop [TODO]

Carousel Loop Support

It is the year 2116, and, after many little wars sparked by overpopulation, life is very different from what we know today.

Everyone is born on the same day, and is given a unique combination of name and generation number, and each citizen is given a Geodesic DOM structure where they can live a hedonistic life. Until they reach age 21, at which point it's time to be "renewed." For on that day a new generation of citizens is born, and each newborn is also given a name followed by a new generation number, one higher than the last. Many of the names match the previous generation's name. Matching names is generally a sign that they share many of the same traits. The new generation is also given a promise to inhabit the very same Geodesic DOM structures the previous generation was inhabiting.

When the citizens reach their Last Day, they get to fill out a preference card for what should happen to their body and soul on the fateful next day, when the crystal embedded in their palm turns black.

Let's say Jessica 6, for example, has reached her Last Day. Jessica 6 can request that should a newborn be assigned to her Geodesic DOM, Jessica 6 should be automatically cremated, so as to give the next generation a fresh start, whether the person's name is Jessica 7 or Doyle 7. Or Jessica 6 could request that should the new inhabitant be Jessica 7, to please merge her memories into the memories of Jessica 7, otherwise Jessica 6 should be cremated. Or Jessica 6, being open to all newcomers, could ask that her memories be merged in, regardless of who inhabit her DOM next. Jessica 6 can also request that if no one is assigned to her Geodesic DOM, that she can become a "runner" and hide, so her memories can be merged at a later time.

The new generation, though, witnessing all this in a Rawlsian veil of ignorance, also get the chance to fill out a preference card, and their will generally takes precedence over the one-day-left living generation. They can request that they would like to absorb the wisdom, strength, and other resources of the previous generation, but only if their names match, and reside in the same DOM. Or they can ask that they be assigned any old Geodesic DOM, but they would still like to absorb the life spirits of the previous occupant. Or, being concerned that this would cause them confusion, request that the previous occupant be cremated. Doing so means they start out penniless, but on the other hand carrying no out-dated "baggage" with them.

Tentative proposal:

interface ItemStatus{

version: number | string;

breaking: boolean;

inScope: boolean;

identity: number | string;

}

LoganLoop(

template: HTMLTemplateElement | [symbol, string],

ctx: RenderContext,

items: any[],

itemStatus: item: any => ItemStatus,

target: HTMLElement,

initTransform: TransformValueOptions,

updateTransform: TransformValueOptions = initTransform

)

If an item's status is "breaking", the previously generated DOM fragment generated from that item is deleted first. If an item's inScope is false, it will be hidden (or remain deleted if breaking). No transform applied. If no change in version, no change is made to the DOM fragment generated from that item. If item is missing, DOM element is hidden, no transform.

Order of items doesn't matter after initialization --

Non-validated conjecture -- it is cheaper to set the order via css vs rearranging DOM source order. But not ideal for keyboard navigation so maybe have some serious debouncing followed by specialized function that makes source order match css order in the background.

Is limited support enough? -- rambling soliloquy

NB: trans-render follows a modular pattern. Beyond the most basic functionality, most of the syntax is supported via "plugins" so that alternative implementations can be adopted. Open ended extending of functionality is also supported. That includes some functionality already discussed, such as conditional templates.

There is quite a bit of nuance that applies to seemingly simple functionality, such as conditional display, and, even more so, repeating content. In the case of conditional display -- what should happen to content that is no longer visible? Delete it? Hide it? If hiding it seems best, by what mechanism? How can we ensure that this hidden content isn't tapping the cpu unnecessarily? If deleting it, how do we restore the same exact state the content was in should the conditions change back? How can we integrate the original HTML provided by the server, in HTML format? Etc.

There are two competing approaches for defining these more complex structures -- XML/HTML/template -- first, vs JS -- first.

In the context of build-less web components (which TR is designed to support), the preference for HTML-first vs JS-first will tend to be driven (or skewed) by what native import mechanisms are available. If, without a build process, shared functionality can only be imported via JS, then this will tend to make it more convenient to provide and invest in rich JS-centric libraries for doing fancy things like rapid list updates or sophisticated conditional display. In a JS-first world (discounting however SSR is categorized), these can take the form of directives for tagged template literal libraries, for example. In a HTML-first world these can take the form of web components, or custom attributes like v-for.

Should HTML modules become a thing, this could re-kindle interest in using markup tags, as opposed to JS expressions, to express loop and conditional logic, like those provided by build-oriented frameworks like VueJS or web component libraries like Lightning. Now, choosing between competing approaches (e.g. virtual scrolling vs more accessible solutions) becomes as simple as replacing one tag-name, or attribute pattern, for another.

Including some indication of looping or conditional display in the pristine HTML markup also seems semantically meaningful, more so than property and event binding.

trans-render straddles the fence somewhat between html-first vs js-first. It is banking on the hope that HTML Modules will arrive someday, which would free us from having to map tagged template literal expressions into template parts. This would tend to promote the idea of using web components or custom attributes to define conditional or repeating structures.

In the case of repeating structures, especially, a dilemma arises: Sure, we know we need to bind to some array, like items, but now how do we bind items within the loop to HTML elements? JS-first or HTML-first? If using a template only markup system, like vueJS, or (non lit-html Polymer), the answer is fairly straight-forward, but it does mean the web component is tightly coupled to particular binding syntax.

trans-render is a fence straddler, as far as HTML-first vs JS (or JSON) - first. Should HTML Modules become officially dead, this would likely warrant putting more effort into plugins that specialize in different approaches to conditional and/or repeating content.

But even in this dastardly world, there still seems to be a benefit in developing specialized logic that can effectively handle looping or conditional logic, including different scenarios / preferences, but which isn't tightly coupled to a particular binding syntax. In other words, using web components for defining complex looping and conditional structures still has value, due to its interop nature (but as we will see below, has some disadvantages).

And even if HTML Modules happen, what would a trans-render-friendly web component repeat component look like, that could also provide inline binding support for various syntaxes?

We can assume the definition of what each item should render would be template based. We also want the syntax to be succinct. This poses a challenge for web components.

vue, aurelia, angular have the most succinct markup when it comes to conditionals and loop. It is one-level deep.

This is followed by JSX, svelte, xslt, tagged template literals. They are two-levels deep.

If we were to make a looping web component, and define the repeating content via template, it would become the most verbose:

<ul>

<my-repeater-element>

<template>

<li>{item.name}</li>

</template>

</my-repeater-element>

</ul>

By my counting the loop above is three levels deep. That's a hard sell.

So what to do?

Option 1 Supporting two-level-deep repeat

One option is to "enhance" the template element, either using the controversial built-in "is" solution, which Apple rejects, or something like xtal-decor:

<ul>

<proxy-props for=for items={model.items}></proxy-props>

<template be-for>

<li>{item.name}</li>

</template>

</ul>

which, honestly, is still three-levels deep (sigh). The proxy-props tag is necessary to "pipe" property settings to the proxy attached to the template element (without polluting the native template tag with custom properties).

Anyway, a base, abstract component that extends xtal-decor (for example) could be used, providing an abstract (TypeScript supports this) "render" method that needs implementing according to the syntactical tastes of the developer.

So a trans-render version of the loop above would look like:

<ul>

<template be-for='{

"items": [{"name":"fergie"},{"name":"will.i.am"}]}

"transform": {"li": "ctx.item.name"}

'}>

<li></li>

</template>

</ul>

Option 2 -- Enhance trans-render

Another (not mutually exclusive) alternative is to create a two step process -- a one-time (build time or run time) template to template transform, followed by repeated template instantiation transformations (per custom element instantiation, for example). The human-edited template syntax could look like:

<ul>

<li foreach item in items>

<span data-field=item.name><span>

</li>

</ul>

Then TR could be used to transform the syntax above into something like:

<ul>

<my-repeater-element collection-name=items>

<template>

<li foreach item in items>

<span data-field=item.name><span>

</li>

</template>

</my-repeater-element>

</ul>

my-repeater-element would then examine the contents of template, see the "foreach item in items" attributes, interpret them, and then delete them, in order for the HTML to be 100% kosher.

What trans-render is currently missing, then, that seems quite useful, is built-in support for wrapping inside other multi-level tags, or a template.

I.e. we want to somehow be able to say: Define a wrapping template that looks like:

const trePatternTransformer = ({for, inner}) => /* html */`

<my-repeater-element -items>

<template>

${inner}

</template>

</my-repeater-element>

`;

and apply this wrapping template when you encounter attribute: tr:use=mre.

Basically, trans-render needs "snippet" support. Or the kind of slot support ShadowDOM supports, but without ShadowDOM.

Adjacent template insertion

insertAdjacentTemplate(template: HTMLTemplateElement, target: Element, position: InsertPosition)

This function is modeled after insertAdjacentElement / insertAdjacentHTML. Only here we are able to insert a template. By using the preferred "afterEnd" as the insert position, the trans-rendering will be able to process those nodes like any other nodes.

Ergonomic Tag Creation

appendTag<T extends HTMLElement>(container: HTMLElement, name: string, config: PEAUnionSettings<T> | DecorateArgs<T> /* untested */) : HTMLElement

Just saves a tiny bit of boiler plate (document.createElement, container.appendChild)

Text Searching

split(target: HTMLElement, textContent: string, search: string | null | undefined)

Splits text based on search into styleable spans with class "match" and sets the innerHTML to this partitioned content. The second argument, 'textContent' should not contain any HTML tags in it (but that is left to the caller to ensure).

Content Swapping, Part I

replaceElementWithTemplate(target: HTMLElement, ctx: RenderContext, template: HTMLTemplateElement | [symbol, string])

During pipeline processing, replace a tag with a template. The original tag goes into ctx.replacedElement.

For the template parameter, you can either pass in a template object, or an html string / symbol pair. The symbol is required so the template can be cached.

Content Swapping, Part II

replaceTargetWithTag<TargetType extends HTMLElement = HTMLElement, ReplacingTagType extends HTMLElement = HTMLElement>

(target: TargetType, ctx: RenderContext, tag: string, preSwapCallback?: (el: ReplacingTagType) => void)

During pipeline processing, replace a tag with another tag. The original tag goes into ctx.replacedElement

Piercing into ShadowDOM

pierce<TargetType extends HTMLElement = HTMLElement>(el: TargetType, ctx: RenderContext, targetTransform: TransformRules)

... pierces into the shadow root of the target element, and (asynchronously) applies transform rules within the shadow root. If the target element is a custom element, there is a delay to wait for the custom element to be upgraded, but there is perhaps a bit of timing fragility that accompanies this dangerous (but necessary as a last resort) function.

NB Doing this breaks any and all warranties from the component / template being surgically altered.

Advanced utility functions

Property merging

Object.assign, and its modern abbreviated variations, provides a quite declarative feeling when populating an object with values. Unfortunately, Object.assign is a fast shallow merge. An alternative to object.assign are more nuanced deep merge functions like JQuery.extends, or lodash merge, which domMerge draws inspiration from.

The function domMerge provides similar help.

The (tentative) signature is

export function domMerge<(target: HTMLElement, vals: Vals): void

where

export interface Vals {

attribs?: { [key: string]: string | boolean | number };

propVals?: object;

}

Behavior enhancement

Vue (with common roots from Polymer 1) provides an elegant way of turning an existing DOM element into a kind of anonymous custom element. The alternative to this is the "is" built-in custom element api, which, while implemented in two of the three major browsers, remains strongly opposed by the third, and the reasons seem, to my non-expert ears, to have some merit.

Even if the built-ins do become a standard, I still think the "decorate" function, described below, would come in handy for less formal occasions.

Tentative Signature:

export function decorate(

target: HTMLElement,

source: DecorateArgs

)

where

export interface DecorateArgs extends Vals{

propDefs?: object,

methods?: {[key: string] : Function},

on?: {[key: string] : (e: Event) => void},

}

For example:

<div id="decorateTest">

<button>Test</button>

</div>

<script type="module">

import {decorate} from '../decorate.js';

import {init, attribs} from '../init.js';

init(decorateTest, {

Transform: {

div: {

button: ({target}) => decorate(target, {

propVals:{

textContent: 'Hello',

},

attribs: {

title: 'Hello, world'

},

propDefs:{

count: 0

},

on:{

click: function(e){

this.count++;

}

},

methods:{

onPropsChange(){

alert(this.count)

}

}

})

}

}

})

</script>

decorate can also attach behaviors to custom elements, not just native elements, in a decorative way.

Avoiding namespace collisions

Reflections on the Revolutionary Extensible Web Manifesto

NB: All names, characters, and incidents portrayed in the following discussion are fictitious. No identification with actual persons (living or deceased), places, buildings, and products is intended or should be inferred. No person or entity associated with this discussion received payment or anything of value, or entered into any agreement, in connection with the depiction of tobacco products. No animals were harmed in formulating the points discussed below.In a web-loving land, there was a kingdom that held sway over a large portion of the greatest minds, who in turn guided career choices of the common folk. The kingdom's main income derived from a most admirable goal -- keeping friends and family in touch. The kingdom was ruled by conservatives. "Edmund Burke" conservatives, who didn't see the appeal of allowing heretics to join freely in their kingdom. They were tolerant, mind you. If you were not a tax-paying subject born to a family of the kingdom, i.e. a heretic, and you wanted to visit their kingdom, you could do so. You only had to be heavily surrounded by guards, who would translate what you had to say, and vice versa, into Essex, the de-facto language of the web, according to the kingdom's elites.The heretics called these conservatives unflattering words like "reactionaries."

"Why can't we speak directly to your subjects? What are you afraid of?" the counter-cultural heretics would plead.

The ruling elites countered with fancy words like "heuristics" and "smoosh." "We've put our greatest minds to the problem, and, quite frankly, they're stumped. We don't see how we can let you speak freely without corrupting the language of the web. The web rules over all of us, and what if the web wants to introduce an attribute that is already in heavy use? What are we to do then? Don't you see? We are the true lovers of the web. We are protecting the web, so it can continue to evolve and flourish."

Which all sounded like a good faith argument. But why, at least one heretic thought, has the main web site used to bind family and friends together introduced the following global constants, which surely could cause problems if the web wanted to evolve:

A subset of global constants.

meta_referrer

pageTitle

u_0_11

u_0_11

u_0_11

u_0_11

u_0_11

u_0_12

u_0_13

u_0_14

u_0_15

u_0_16

u_0_17

pagelet_bluebar

blueBarDOMInspector

login_form

pass

loginbutton

u_0_2

u_0_3

u_0_4

lgnjs

locale

prefill_contact_point

prefill_source

prefill_type

globalContainer

content

reg_box

reg_error

reg_error_inner

reg

reg_form_box

fullname_field

u_0_b

u_0_c

u_0_d

u_0_e

fullname_error_msg

u_0_f

u_0_g

u_0_h

u_0_i

u_0_j

u_0_k

u_0_l

u_0_m

password_field

u_0_n

u_0_o

u_0_p

u_0_q

month

day

year

birthday-help

u_0_r

u_0_s

u_0_9

u_0_a

u_0_t

terms-link

privacy-link

cookie-use-link

u_0_u

u_0_v

referrer

asked_to_login

terms

ns

ri

action_dialog_shown

reg_instance

contactpoint_label

ignore

locale

reg_captcha

security_check_header

outer_captcha_box

captcha_box

captcha_response_error

captcha

captcha_persist_data

captcha_response

captca-recaptcha

captcha_whats_this

captcha_buttons

u_0_w

u_0_x

u_0_y

reg_pages_msg

u_0_z

u_0_10

pageFooter

contentCurve

js_0

u_0_18

u_0_19And why does the kingdom not want to empower its subjects to choose for themselves if this is a valid concern?

Now I do think this is a concern to consider. Focusing on the decorate functionality described above, the intention here is not to provide a formal extension mechanism, as the built-in custom element "is" extension proposal provides (and which Apple tirelessly objects to), but rather a one-time duct tape type solution. Whether adding a property to a native element, or to an existing custom element, to err on the side of caution, the code doesn't pass the property or method call on to the element it is decorating.

NB If:

- You are slapping properties onto an existing native HTML element, and:

- The existing native HTML element might, in the future, adopt properties / methods with the same name.

Then it's a good idea to consider making use of Symbols:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0">

<meta http-equiv="X-UA-Compatible" content="ie=edge">

<title>Document</title>

</head>

<body>

<div id="decorateTest">

<button>Test</button>

</div>

<script type="module">

import {decorate, attribs} from '../decorate.js';

import {init} from '../init.js';

const count = Symbol('count');

const myMethod = Symbol('myMethod');

init(decorateTest, {

Transform: {

button: ({target}) => decorate(target, {

propVals:{

textContent: 'Hello',

},

attribs:{

title: "Hello, world"

},

propDefs:{

[count]: 0

},

on:{

click: function(e){

this[count]++;

}

},

methods:{

onPropsChange(){

this[myMethod]();

},

[myMethod](){

alert(this[count]);

}

}

})

}

})

</script>

</body>

</html>

The syntax isn't that much more complicated, but it is probably harder to troubleshoot if using symbols, so use your best judgment. Perhaps start properties and methods with an underscore if you wish to preserve the easy debugging capabilities. You can also use Symbol.for('count'), which kind of meets halfway between the two approaches.

NB: There appears to be serious flaw as far as symbols and imports. If you find yourself importing a symbol from another file, even from the same package, you are in for a bumpy ride, from my experience, especially when using a bare import server plug-in like es-dev-server. I've raised the issue here and there. As was suggested in the second link, perhaps the solution is to use Symbol.for in combination with a guid, which seems wasteful bandwidth wise, and makes debugging more difficult, perhaps.

Even more indirection

The render context which the init function works with provides a "symbols" property for storing symbols. The transform does look a little scary at first, but hopefully it's manageable:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0">

<meta http-equiv="X-UA-Compatible" content="ie=edge">

<title>Document</title>

</head>

<body>

<div id="decorateTest">

<button>Test</button>

</div>

<script type="module">

import {decorate} from '../decorate.js';

import {init} from '../init.js';

init(decorateTest, {

symbols: {

count: Symbol('count'),

myMethod: Symbol('myMethod')

},

Transform: {

button: ({target, ctx}) => decorate(target, {

propVals: {

textContent: 'Hello',

},

attribs:{

title: "Hello, world"

},

propDefs:{

[ctx.symbols['count']]: 0

},

on:{

click: function(e){

this[ctx.symbols['count']]++;

}

},

methods:{

onPropsChange(){

this[ctx.symbols['myMethod']]();

},

[ctx.symbols['myMethod']](){

alert(this[ctx.symbols['count']]);

}

}

})

}

})

</script>

</body>

</html>

Ramblings From the Department of Faulty Analogies

When defining an HTML based user interface, the question arises whether styles should be inlined in the markup or kept separate in style tags and/or CSS files.

The ability to keep the styles separate from the HTML does not invalidate support for inline styles. The browser supports both, and probably always will.

Likewise, arguing for the benefits of this library is not in any way meant to disparage the usefulness of the current prevailing orthodoxy of including the binding / formatting instructions in the markup. I would be delighted to see the template instantiation proposal, with support for inline binding, added to the arsenal of tools developers could use. Should that proposal come to fruition, this library could be used to augment the native template instantiation process.

And in fact, the library described here is quite open ended. Until template instantiation becomes built into the browser, this library could be used as a stand-in. Once template instantiation is built into the browser, this library's scope could reduce, but could continue to supplement the native support when needed.

For example, in the second example above, the core "init" function described here has nothing special to offer in terms of string interpolation, since CSS matching provides no help:

<div>Hello {{Name}}</div>

We provide a small helper function "interpolate" for this purpose, but as this is a fundamental use case for template instantiation, and as this library doesn't add much "value-add" for that use case, native template instantiation could be used as a first round of processing. And where it makes sense to tightly couple the binding to the template, use it there as well, followed by a binding step using this library. Just as use of inline styles, supplemented by css style tags/files (or the other way around) is something seen quite often.

A question in my mind, is how does this rendering approach fit in with web components (I'm going to take a leap here and assume that HTML Modules / Imports in some form makes it into browsers, even though I think the discussion still has some relevance without that).

I think this alternative approach can provide value, by providing a process for "Pipeline Rendering": Rendering starts with an HTML template element, which produces transformed markup using TR or (hopefully soon) native template instantiation. Then consuming / extending web components could insert additional bindings via the CSS-matching transformations this library provides.

To aid with this process, the transform function provides a rendering options parameter, which contains an optional "initializedCallback" and "updatedCallback" option. This allows a pipeline processing sequence to be set up, similar in concept to Apache Cocoon.

Client-side JS faster than SSR?

Another interesting case to consider is this Periodic Table Codepen example. Being what it is, it is no surprise that there's a lot of repetitive HTML markup needed to define the table.

An intriguing question, is this: Could this be the first known scenario in the history of the planet, where rendering time (including first paint) would be improved rather than degraded with the help of client-side JavaScript?

The proper, natural instinct of a good modern developer, including the author of the codepen, is to generate the HTML from a concise data format using a server-side language (pug).

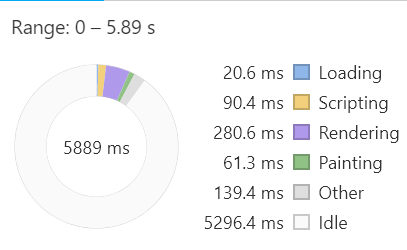

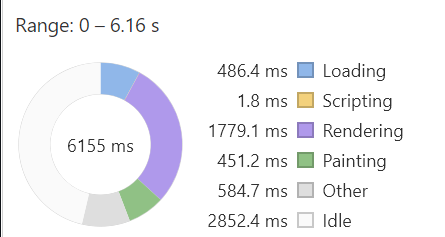

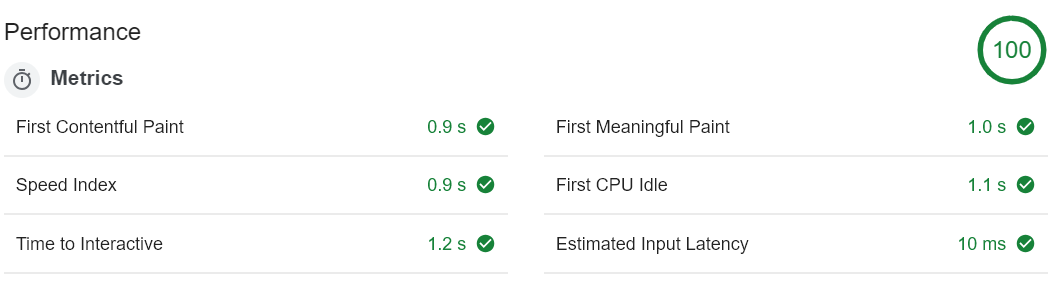

But using this library, and cloning some repetitive templates on the client side, reduces download size from 16kb to 14kb, and may improve other performance metrics as well. These are the performance results my copy of chrome captures, after opening in an incognito window, and throttling cpu to 6x and slow 3g network.

Trans-Rendering:

Original:

You can compare the two here: This link uses client-side trans-rendering. This link uses all static html

Results are a bit unpredictable, and usually the differences are less dramatic.

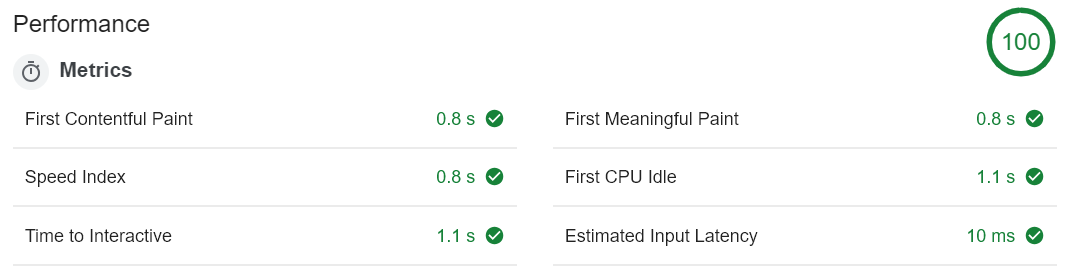

Lighthouse scores also provide evidence that trans-rendering improves performance.

Trans-Rendering:

Original:

Once in a while the scores match, but most of the time the scores above are what is seen.

So the difference isn't dramatic, but it is statistically significant, in my opinion.

See this side-by-side comparison for more evidence of the benefits.

trans-render the web component

A web component wrapper around the functions described here is available.

Example syntax

If you are here what appears next should work: